This post summarises a recent paper, “Protecting Society from AI Misuse: When are Restrictions on Capabilities Warranted?”

GovAI research blog posts represent the views of their authors, rather than the views of the organisation.

Introduction

Recent advancements in AI have enabled impressive new capabilities, as well as new avenues to cause harm. Though experts have long warned about risks from the misuse of AI, the development of increasingly powerful systems has made the potential for such harms more widely felt. For instance, in the United States, Senator Blumenthal recently began a Senate hearing by showing how existing AI systems can be used to impersonate him. Last week, the AI company Anthropic reported that they have begun evaluating whether their systems could be used to design biological weapons.

To address growing risks from misuse, we will likely need policies and best practices that shape what AI systems are developed, who can access them, and how they can be used. We call these “capabilities interventions.”

Unfortunately, capabilities interventions almost always have the unintended effect of hindering some beneficial uses. Nonetheless, we still argue that — at least for certain particularly high-risk systems — these sorts of interventions will be increasingly warranted as potential harms from AI systems increase in severity.

The Growing Risk of Misuse

Some existing AI systems – including large language models (LLMs), image and audio generation systems, and drug discovery systems – already have clear potential for misuse. For instance, LLMs can speed up and scale up spear phishing cyber attacks to target individuals more effectively. Image and audio generation models can create harmful content like revenge porn or misleading “deepfakes” of politicians. Drug discovery models can be used to design dangerous novel toxins: for example, researchers used one of these models to discover over 40,000 potential toxins, with some predicted to be deadlier than the nerve agent VX.

As AI systems grow more capable across a wide range of tasks, we should expect some of them to become more capable of performing harmful tasks as well. Although we cannot predict precisely what capabilities will emerge, experts have raised a number of concerning near- and medium-term possibilities. For instance, LLMs might be used to develop sophisticated malware. Video-generation systems could allow users to generate deepfake videos of politicians that are practically indistinguishable from reality. AI systems intended for scientific research could be used to design biological weapons with more destructive potential than known pathogens. Other novel risks will likely emerge as well. For instance, a recent paper highlights the potential for extreme risks from general-purpose AI systems capable of deception and manipulation.

Three Approaches to Reducing Misuse Risk

Developers and governments will need to adopt practices and policies (“interventions”) that reduce risks from misuse. At the same time, they will also need to avoid interfering too much with beneficial uses of AI.

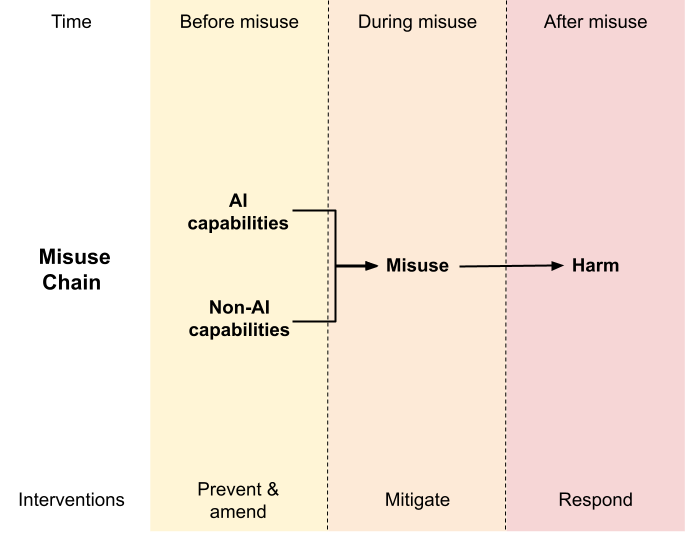

To help decision-makers navigate this dilemma, we propose a conceptual framework we refer to as the “Misuse Chain”. The Misuse Chain breaks the misuse of AI down into three stages, which can be targeted by different interventions.

Capabilities interventions target the first stage of the Misuse Chain, in which malicious actors gain access to the capabilities needed to cause harm. For instance, if an AI company wishes to make it harder for bad actors to create non-consensual pornographic deepfakes, it can introduce safeguards that block its image generation systems from generating sexual imagery. It can also take additional measures to prevent users from removing these safeguards, for instance by deciding not to open-source the systems (i.e. make them freely available for others to download and modify).

Harm mitigation interventions target the next stage in the Misuse Chain, when capabilities are misused and produce harm. For example, in the case of pornographic deepfakes, harm can be mitigated by identifying the images and preventing them from being shared on social media.

Harm response interventions target the final stage of the Misuse Chain, in which bad actors experience consequences of their actions and victims receive remedies. For example, people caught using AI systems to generate explicit images of minors could not only have their access revoked but also face punishment through the legal system. Here, the aim is to deter future attempts at misuse or rectify the harm it has already caused.

Capabilities Interventions and the Misuse-Use Tradeoff

Interventions that limit risks from misuse can also hinder beneficial uses; they are subject to what we call the “Misuse-Use Tradeoff”. As interventions move “upstream” along the Misuse Chain — and more directly affect the core capabilities that enable malicious actors to cause harm — they tend to become less targeted and exhibit more significant trade-offs. Interventions near the top of the chain can limit entire classes of use.

Take, for example, content policies for large language models that prohibit the model from outputting any text related to violence. Such a blunt policy tool may prevent harmful content from being generated, but it also prevents the model from being used to analyse or generate fictional works that reference violence. This is an undesirable side effect.

However, if an AI system can be used to cause severe harm, then the benefits of even fairly blunt capability interventions may outweigh the costs.

Why Capabilities Interventions May Be Increasingly Necessary

Where possible, developers and policymakers should prefer harm mitigation and harm response interventions. These interventions are often more targeted, meaning that they are more effective at reducing misuse without substantially limiting beneficial use.

However, these sorts of interventions are not always sufficient. There are some situations where capabilities interventions will be warranted, even if other interventions are already in place. In broad terms, we believe that capabilities interventions are most warranted when some or all of the following conditions hold:

- The harms from misuse are especially significant. If the potential harms from misuse significantly outweigh the benefits from use, then capabilities interventions may be justified even if they meaningfully reduce beneficial use.

- Other approaches to reducing misuse have limited efficacy if applied alone. If interventions at other stages are not very effective, then capabilities interventions will be less redundant.

- It is possible to restrict access to capabilities in a targeted way. Though capabilities interventions tend to impact both misuse and use, some have little to no impact on legitimate use. For example, AI developers can monitor systems’ outputs to flag users who consistently produce inappropriate content and adjust their access accordingly. If the content classification method is reliable enough, this intervention may have little effect on most users. In such cases, the argument for capability interventions may be particularly strong.

Ultimately, as risks from the misuse of AI continue to grow, the overall case for adopting some capability interventions will likely become stronger. Progress in developing structured access techniques, which limit capability access in finely targeted ways, could further strengthen the case.

Varieties of Capability Interventions

In practice, to reduce misuse risk, there are several varieties of capability interventions that developers and policymakers could pursue. Here, we give three examples.

- Limiting the open source sharing of certain AI systems. Open-sourcing an AI system makes it harder to prevent users from removing safeguards, reintroducing removed capabilities, or introducing further dangerous capabilities. It is also impossible to undo the release of a system that has been open-sourced, even if severe harms from misuse start to emerge. Therefore, it will sometimes be appropriate for developers to refrain from open-sourcing high-risk AI systems – and instead opt for structured access approaches when releasing the systems. In sufficiently consequential cases, governments may even wish to require the use of structured access approaches.

- Limiting the sharing or development of certain AI systems altogether. In some cases, for instance when an AI system is intentionally designed to cause harm, the right decision will be to refrain from development and release altogether. If the problem of emergent dangerous capabilities becomes sufficiently severe, then it may also become wise to refrain from developing and releasing certain kinds of dual-use AI systems. As discussed above, in sufficiently high-risk cases, governments may wish to consider regulatory options.

- Limit access to inputs needed to create powerful AI systems. Companies and governments can also make it harder for certain actors to access inputs (such as computing hardware) that are required to develop harmful AI systems. For example, the US recently announced a series of export controls on AI-relevant hardware entering China, in part to curb what it considers Chinese misuse of AI in the surveillance and military domains. Analogously, cloud computing providers could also introduce Know Your Customer schemes to ensure their hardware is not being used to develop or deploy harmful systems.

Conclusion

As AI systems become more advanced, the potential for misuse will grow. Balancing trade-offs between reducing misuse risks and enabling beneficial uses will be crucial. Although harm mitigation and harm response interventions often have smaller side effects, interventions that limit access to certain AI capabilities will probably become increasingly warranted.

AI labs, governments, and other decision makers should be prepared to increasingly limit access to AI capabilities that lend themselves to misuse. Certain risks from AI will likely be too great to ignore, even if that means we must impede on legitimate use. These actors should also work on building up processes for determining when capabilities interventions are warranted. Furthermore, they should invest in developing interventions that further reduce the Misuse-Use Tradeoff. Continued research could yield better tools for preventing dangerous capabilities from ending up in the wrong hands, without also preventing beneficial capabilities from ending up in the right hands.